|

Photography courses were first offered at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 1902. The production of the Images from Science project is a fitting tribute to 100 years of photographic activities in this university. The School of Photographic Arts and Sciences has a rich history of contributions to photographic education and exploration. This project is one more example of many significant achievements that have come out of the school and its faculty. The imagination that led to Images from Science could only have come from individuals who are committed to excellence in photographic art and science. RIT, and the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences in particular, are proud to be associated with the important and beautiful work represented in this exhibition. On behalf of the university, I thank Professor Andrew Davidhazy and Professor Michael Peres for their impressive achievement. Dr. Joan Stone

Preface - A Brief History Silver halide photography, invented in 1839, depicts scenes and subjects with a precision that drawing cannot approach. Soon after photography's invention, scientists, researchers, and physicians began using it to document and share certain aspects of their work, and they have continued to do so ever since. Their images, usually created in laboratories far removed from the eye of the general public, have seldom won the wide recognition and acceptance accorded other photographic genres. Though a few scientific photographers, Eadweard Muybridge (1867-1904), Dr. Harold Edgerton (1903-1990), and Lennart Nilsson (b. 1922) among them, have won some measure of fame among admirers of photography, most remain unrecognized outside the circle of their immediate peers. Images from Science has been created to promote a wider appreciation of scientific photography by showcasing beautiful, data-rich, but rarely seen images drawn from oceanography, geology, biology, engineering, medicine, and physics. We first conceived the idea in spring 2001 during a casual conversation over coffee. By mid-summer 2001 we had determined that the project would comprise three major components: a photographic exhibition at Rochester Institute of Technology, a related Web gallery, and a four-color printed catalogue, all budgeted at $17,000, none of which was in hand. We chose the Internet as our principal promotional tool, hoping that it would provide an efficient, low-cost means of attracting the worldwide interest and participation we sorely wanted but were hardly assured of getting. Our Web site described the project this way: Organized to showcase photographs made in pursuit of science, IMAGES from SCIENCE welcomes pictures made with any imaging tools as the source, not only traditional photographic ones. This invitation, the exhibition's promotion and image contribution, etc., will primarily be conducted relying on the Internet. We would appreciate you sharing this announcement with others to accomplish our goal of developing this international exhibition. Acceptance into this juried show will be based on the photograph's impact, the image's aesthetics, the degree of difficulty in the making of the photograph, as well as other related criteria. A maximum of four images may be submitted for judging. JPEG files with a resolution of about 640 x 480 pixels (or equivalent) should be mailed to RITphoto@rit.edu by March 30, 2002. A frighteningly small trickle of submissions began arriving in August 2001, and by the end of November a mere three photographers had submitted less than a dozen images in all. Faced with the real prospect of humiliation, we worked hard during RIT's January 2002 recess to spread the word about the project. A flurry of responses began arriving around February 20. In the week before the judging deadline, nearly 60 photographers submitted a total of some 180 pictures. Between then and February 27 another 23 entries were submitted, by which time the exhibition's computer account was swamped by the deluge of image data. When the final tally was in, 87 photographers representing 14 countries had submitted more than 290 pictures for consideration. Judges were invited

at various stages of the project. Dr. David Malin, having agreed to write

the guest essay for the catalogue, rightly argued that an international

project required international judges. Lacking funds to support travel,

we again turned to the Internet, developing a judges' Web site complete

with all entries and support materials. Judges were selected to represent

a wide range of attitudes about pictures and were ultimately drawn from

the ranks of scientists, scientific photographers, educators, practicing

artists, and photographic editors. Most of them represented organizations

whose indirect involvement lent additional prestige and validity to our

project. Each judge received the following instructions:

Fifty-eight photographs were ultimately chosen for inclusion. As we complete the production of this catalogue, we have seen our simple idea become something far greater than we anticipated. We congratulate our new colleagues whose aesthetic and scientific achievements made this exhibition and catalogue possible, and thank them for trusting us with their images.

Professor Michael

Peres

Professor Andrew

Davidhazy

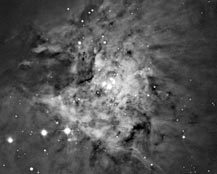

Introduction - Guest Essay by Dr. David Malin The making of images, representations of the world around us, seems to have been part of the life of our species ever since we evolved to the point of being identifiably human. One could argue that it is an enduring and distinct human characteristic to attempt to understand nature by capturing some kind of picture of it. Thirty thousand or more years ago our ancestors left tangible evidence of this in their cave paintings. It is not surprising that no other creatures seem to create such pictures, for it requires considerable dexterity and intellect to translate a dynamic, colorful, three-dimensional scene into the static, two-dimensional, monochromatic outline typical of cave paintings. Those of us who, despite thousands of generations of evolution, have failed to develop such skill are fortunate in that we can still enjoy, interpret, and respond to these images and recreate elements of the original tableau in our mind's eye. Many people would call ability in observation and interpretation the essence of art, but it is also the essence of scientific imagery. What differs is the motivation of the creator. The eye of the interpreter is a different matter altogether, and is an underlying theme of the Images from Science project. Those of our ancestors who chose to represent some aspect of their experience on the rough surfaces of cave walls did so not from any scientific motivation, but from a desire, one much like that of today's artists and photographers, to record something of the world in which they lived. Nonetheless, their dramatic pictures are scientifically useful because they reveal information about long-gone events, environments, cultures and traditions. The artistry of these pictures cannot be ignored, but it is their improbable existence that perhaps most captures the imagination. Their information content, which may not reveal itself at first glance, comes as a welcome bonus. Objectivity is the most important requirement of illustration claiming to represent some aspect of science, but illustration is not an objective business. The choice of the method, and the moment of creation will always leave something of the creator's stamp on a picture. The mere selections of field of view, magnification, and focus setting on a microscope inevitably reflect choices made by the microscopist before the shutter is pressed to capture the image. To be useful, the record must be presented as a print, a slide, or in any of a dozen other formats, each of which imposes a further layer of subjectivity. Many of us see this not as a limitation of scientific illustration but as an enormous advantage. It allows us the freedom to make our pictures interesting, not only to other scientists but to members of the lay public who may be utterly indifferent to the processes of science. Astronomy is a great exemplar of this, especially the stream of exciting images emerging daily from the Hubble Space Telescope. These are mostly made from data obtained for scientific purposes, but their aesthetic appeal cannot be ignored and is actively exploited by NASA. Astronomical images from a much earlier age, however, can tell us something about the subjective nature of scientific illustration and about the pace of events in science today. science from art The making of pictures in the service of science has a long history. Though we now think of images from science primarily in terms of photography or its electronic equivalent, in the days before photography much wonderful and quite beautiful work was done with pen, paint, and paper. Many examples of such work, including drawings and paintings of plants, animals, and birds, especially those found in the new worlds of the Americas and Australia, are available from all the sciences active prior to the introduction of photography (circa 1840). These images, nowadays valued more for their artistry than their scientific content, were often the sole means of conveying visual information about exotic locales in an age when travel was mostly open only to the adventurous (and occasionally unfortunate) few. Some artist-scientists devoted endless hours to portraying not such clearly visible (if often reluctant) subjects as birds and beasts or images on the threshold of human vision. Some of these images were unseen in all but the largest telescopes of their day, distant places that, while part of the natural world, could not be visited or studied up close. The study of the stars, nebulae, and galaxies has some unique characteristics. Firstly, it is a purely observational science. Fortunately we cannot experiment with the stars; if we could, the closest star, the Sun, would be our most likely subject. Because we are currently conducting an uncontrolled experiment of uncertain outcome with the air and water of our own planet, I feel it would be foolish to trifle with that other essential ingredient of life, the energy from the Sun. Though we dispatch probes to the nearest planets, the rest of the universe is spared our direct intervention for now, so we are obliged to learn about it by looking. Nowadays we look with ever-more-sensitive instruments covering most of the electromagnetic spectrum. It was not always so, and from the invention of the telescope in the early 1600s until about 1880, images of the objects of the night sky were laboriously studied by eye and sketched by hand. At the urging of nineteenth-century England's leading astronomer, Sir John Herschel, the Sun began being monitored daily by means of photography in 1858 or so, but the nighttime astronomical telescopes and photographic emulsions of the time could not support the long exposures needed to photograph faint celestial objects. Herschel was knighted by the young Queen Victoria in June 1838, soon after his return from a four-year expedition to observe the southern skies from Cape Town, South Africa. While there he had made copious notes and detailed drawings of many astronomical objects, among them the famous Orion nebula. We now know this to be the nearest star-forming region, but to Herschel and his contemporaries the Great Nebula in Orion was an enduring mystery, the most conspicuous of thousands of similar but fainter fuzzy objects between the stars. He made meticulous drawings of it with the declared purpose of providing future generations of scientists with a totally objective record of the state of the nebula and the disposition of the stars within it. Herschel hoped that later observations would show changes that might reveal the nature of this curious misty patch. He made his notes and initial sketches in 1832-33, but the results were not widely published until 1847. Fortunately he owned the telescope he used, providing him with more observation time than other colleagues. Though Herschel was very familiar with the photographic experiments of William Henry Fox-Talbot in England, he was surprised to learn in January 1839 of Daguerre's announcement of a practical system invented in France. Within a week of hearing the news, Herschel began making his own photographs. He thereafter consistently encouraged the use of photography to record scientific results and phenomena, but his own interests were in the process rather than its applications. Photography of the night sky remained elusive until a decade after Herschel's death in 1871. In the meantime, other drawings of the Orion nebula were made, most notably in 1860 by William Parsons, third Earl of Rosse, who was also keen to detect changes in the nebula and whose telescope was more powerful than Herschel's. |

Our title-page

image, Lennart Nilsson's picture of the 78-million-year-old flower fossil,

was chosen in tribute to Nilsson's importance as a

Our title-page

image, Lennart Nilsson's picture of the 78-million-year-old flower fossil,

was chosen in tribute to Nilsson's importance as a